An Interview with Sue Evans

by Ann Armbrecht

Sue Evans PhD

is a Senior Lecturer in Complementary and Alternative Medicines

at the University of Tasmania

In early December 2018, I received an email from Sue Evans, an Australian herbalist whom I came to know during the SHP Kickstarter, saying how valuable her students found the SHP resources, especially the videos. I was thrilled to know that the website was being used in this way and asked if she would be willing to share how she used the content on the website and how she taught about the botanical industry more broadly. This interview builds on the AHG panel discussion I facilitated on what US based herbalists can do to address sustainability in the herb industry.

Herbalism in Australia

Ann: Can you talk some about the herbalism in Australia especially in terms of sourcing and manufacturing herbal medicine? And how it differs from the US and Europe?

Sue: The big difference here is that, as practitioners of Western herbal medicine, we don’t use plants that are native to Australia. We use the same materia medica as herbalists in the US and in Europe – and these plants are not found in our native flora.

So wild harvesting here is relatively uncommon, and happens mainly in relation to introduced plants, particularly invasive exotic species. In addition, our herb growing industry is small. Many common medicinals are cultivated here, particularly the Mediterranean plants – think thyme, lavender, rosemary. Echinacea does well, but many others, such as your woods-grown North American plants, are very difficult to grow in our climate.

Harvesting chamomille, photo by Sue Evans.

Individual herbalists have their own herb gardens and some manufacturers source locally cultivated medicinal plants, but overall, our medicines are largely imported. They may be imported as finished products or as dried herbs to be manufactured in Australia. While the herbal industry in Europe and the US is reliant on global trade, in Australia that dependence is greater.

Why don’t we use indigenous plants? Why haven’t Australian indigenous plants been introduced into the materia medica of Western herbal medicine in the way of many North American one? That is a complex topic – I can talk about it another day!

Brown Bottle Herbalists

Ann: What challenges does this create for being a practitioner in Australia?

Sue: It’s a challenge to develop a relationship with a plant as a plant, rather than as a liquid or tablet. And it’s even more of a challenge to understand that plant as part of a larger ecosystem.

We have many ‘brown bottle herbalists’ here – herbalists who know the plant only through the tincture bottles on their dispensary shelves, rather than as a living plant.

Ann: How did you first become interested in sustainability and the herbal products industry?

Sue: I qualified as a medical herbalist in the UK in the early 1980s, and after I returned home I met the herb grower Greg Whitten. At the time Greg was growing herbs on a magical farm, Twin Creeks, in central Victoria, which he shared with a small manufacturer, Michael Gardiner. Greg grew the plants and Michael made the medicines. I learned so much from the time I spent there, about individual plants and about the challenges of working with them.

In the early 1990s both businesses were deeply impacted by regulatory changes that came with the (national) Therapeutic Goods Act. This legislation initiated a period of turmoil, and I was involved with Greg in lobbying on behalf of small growers. We had some minor successes, but this regulation irrevocably changed the face of Australian herbal medicine. There were big winners and big losers.

Sustainability in Trade

In relation to sustainability, while I was aware of issues with individual plants from the 1980s, this concern ramped up in 2005 when I read an article by Alan Hamilton [1] linking sustainability and fair trade with herbal medicine more broadly. It became a matter of urgency to find ways to systematically communicate these issues to students and to my professional community.

Ann: Can you talk some about the course? Who are your students? What kind of content were they most interested in and why? Were sustainability/supply chain/industry issues one section of a larger course? Or a course on its own? Is there anything you’d like to share about how and why you designed the course and what you hoped your students got from it?

Sue: When I had that ‘aha moment’ in 2005, I was teaching herbal medicine within a naturopathic course at Southern Cross University, a state-funded university in Lismore NSW. So, it wasn’t a matter of designing a new course but rather of adapting what I was already teaching to include these issues.

Sustainability and Plant Stories

The joy of teaching materia medica is that as a teacher you are introducing students to the individual plants which are going to be their friends and allies. I like to start this process with a discussion of the plant’s story, its origins and how it grows. So, it wasn’t hard to adapt what I taught to include sustainability considerations for each plant. With each plant, sustainability questions would become part of its story.

Is this plant an annual or a perennial? If it’s perennial, what are the sustainability issues of the part used? If the flower or leaf is the part of the plant is used – fine, the plant can probably be harvested without damage. However, we still need to think about where the plant comes from — is it widespread or rare? Cultivated or only available in the wild?

SCU teaching garden, photo by Sue Evans.

When the root or bark is used, there are other questions. Is this a plant like dandelion, whose growth is widespread, and which comes to maturity relatively quickly? Or is it more like one of the ginsengs, which only grows in very specific areas, and whose growth can take decades?

Can the plant be cultivated or is it mostly wild harvested? Is there anything specific we should consider about its availability?

As practitioners we need to think about the environmental implications of our prescriptions. What are the implications to the environment when we prescribe ginseng or dandelion? Yes, price will give an indication, but it is not the whole story. Why is this plant expensive or inexpensive? How much of its story from farm to pharmacy do we know? How much can we know?

(Note: See Steven Foster’s plant stories on saw palmetto).

More recently life changed for me, as life does, and in 2016 I joined the University of Tasmania. Today, rather than primarily teaching herbalists, I get to teach other healthcare practitioners as well as broad swathe of undergraduate students about complementary medicine products. Ecological implications of using herbal medicines and complementary medicines more broadly continue to be fundamental. This is not just an issue for herbalists (concerns about fish oils, anyone?) though my teaching on the topic is now structured as discrete topics in the units, rather than the consistent drip-feed which was the case when I taught materia medica to future practitioners.

Some of this teaching is to be included in an online, open-source course later this year, meaning the offerings will go international. So that’s exciting.

Resources for Teaching on Sustainability and the Botanical Industry

Ann: How did you go about developing content on sustainability in the herbal industry for use in your teaching?

Sue: When I started including these questions with students, it was a challenge to develop teaching resources which were relevant for my students. I talked with friends and colleagues, searched online for reliable information and made contact with people who shared my concerns. I followed the research, [2][3] and started to look at related issues in my own research. [4][5] However it was mostly a matter of deduction as to which herbs were likely to be of concern because there was so little accessible information that was sufficiently specific.

More recently reliable, non-commercial sites have emerged which can be used as teaching resources. These include the Sustainable Herbs Program, FairWild and the State of the World’s Plants and they have been a boon.

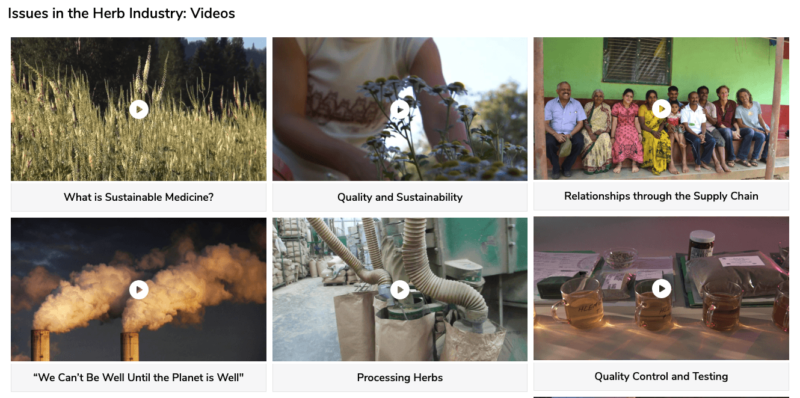

Students love the Sustainable Herbs site, describing it as ‘just superb’, and the videos as ‘very insightful’, giving ‘in-depth look at the herb industry’. The site – and the videos in particular – provide an almost visceral understanding of the complexity of the issues while also challenging their thinking. Here is one reaction:

WOW! Here I was thinking I was just going to ‘do’ some readings and find my whole thinking has changed regarding sourcing and using herbs! Thank you – the course material has really achieved its objective – educating us… The part I found the most thought-provoking was the Sustainable Herbs website, within the tab of what herbalists can do, asking us to consider if our patient really needs that herb and asking if they really need it in that form.

SHP Video Page

(Note: See the SHP guides for teaching and practicing for ideas on where to begin and let us know what other content you would like to see).

(Note: See the SHP guides for teaching and practicing for ideas on where to begin and let us know what other content you would like to see).

Lessons Learned

Ann: What lessons did you take from your experience teaching this?

Sue: Australian practitioners are far from the source of the raw materials in the herbal products they use. Further, there is no culture of transparency in herbal manufacturing, in fact there’s a culture of secrecy regarding sourcing. This means that without certification systems we are dependent on the word of the manufacturer regarding details of sourcing and supply.

There is a high and unquestioning level of trust demonstrated towards herbal manufacturers here. Cathy Avila and I did some research a few years ago into attitudes of Australian herbalists and naturopaths. We found that they depend on manufacturers not only for clinically effective and ethically produced products but also for research information and continuing professional education. [6]

There is no doubt that many manufacturers are of good heart and fine intentions. But without certification systems it is difficult for practitioners to really know whether the products they are using are sustainably harvested and traded ethically.

Further, regulatory requirements mean that herbal medicine is no longer a cottage industry. A number of companies that were started by herbalists as passion projects have been sold to bigger companies, sometimes sold and sold again, so that more of our natural medicine brands are owned by multi-national conglomerates. This reinforces the need for consumers to be critical consumers.

Ann: What were some of the key insights/ ‘ahah’s’ for your students?

Sue: This was one response to the information about herbal sourcing and manufacture from a student last year:

What a thought-provoking process it is, to really dive into the way our herbal medicines are grown & prepared. I must admit, as a naturopath who prescribes liquid herbs often, I don’t give nearly enough thought to where they’ve come from. I rely on the integrity of the Australian companies whose herbs I use. And my clients, in turn, rely on me to be using high quality, sustainable, ethical herbs in their formulas. And neither they nor I are really checking…And I really don’t know, therefore, whether I’m supporting a sustainable & ethical supply. This feels uncomfortable…which is probably the whole point (thanks, Sue!) as I will be asking more questions and not just assuming that “Wildcrafted” on the label is a good thing.

Teaching Sustainability is not an Option

Ann: What advice do you have for other herb/naturopathic teachers around the world about the importance of incorporating lessons on sustainability and industry related topics into their programs?

Sue: Including this in herbal education is not an option. We are herbalists, we make our living from the plants. If we aren’t motivated ethically by needing to ensure that we don’t kill them off in the process, we can be motivated by self-interest. If there are no herbs, there will be no herbalists. These are our tools of trade. No point having knowledge and skills and no herbs.

So, don’t be afraid of exposing that all is not clean and green in our world. Work to make it better. The stakes are too high to do anything else.

First – educate yourself about the issues (you are reading this blog on the SHP site, so that’s a good start!). Then just do it.

- You teach and there’s no room in the curriculum? Make room. You have no authority to make changes? You talk to your students, don’t you? Bring these issues into your conversations with them.

- You’re not a teacher? You may not do formal teaching or lecturing, but you talk to colleagues and clients – discuss these issues with them, encourage them to question the source of the plants they use.

- What questions do you ask your own suppliers? You are the customer. Support suppliers who provide evidence that they share your values.

And if you do all the good things — grow/use plants whose provenance you know/ don’t use endangered herbs — good on you. But this doesn’t give you a free pass. This is still your problem.

You are an herbalist. By choosing that profession (or by it choosing you), you implicitly and explicitly encourage others to use herbs. You are part of the tsunami of demand for medicinal plants. And so you have a responsibility to the plants and you have a responsibility to those who cultivate and harvest the plants you use. Are they getting a fair deal or are they being exploited?

Ginkgo biloba at Avena Botanicals, Maine. Photo by Ann Armbrecht

Be Grateful

Ann: What advice do you have on how to do that most effectively?

Sue: Just keep in mind – by using herbal medicines we acknowledge our dependence on the plant world. We demonstrate our respect for that world by being thoughtful consumers, mindful about our own consumption and that which we recommend. And be forever grateful for the privilege of working with these wonderful plants.

- Hamilton, AC. Medicinal plants, conservation and livelihoods. Biodiversity and Conservation, 2004; 13(8):1477-1517. doi:10.1023/B:BIOC.0000021333.23413.42.

- Booker A, Johnston D, Heinrich M. Value chains of herbal medicines—ethnopharmacological and analytical challenges in a globalizing world. In: PK Mukherjee ed, Evidence-Based Validation of Herbal Medicine. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2015; 29-44.

- Brinckmann J, Hughes K. Ethical trading and fair trade certification: The growing market for botanicals with ecological and social certification. 2010; HerbalGram 88:46-57.

- Bitcon C, Evans S, Avila, C. The re-emergence of grassroots herbalism: an analysis through the blogosphere. Health Sociology Review. 2016; 25(1):108-121.

- Evans S, Avila C. Partners in practice: practitioners’ perceptions of herbal medicine manufacturers revealed through dispensary decisions. Australian Journal of Herbal Medicine. 2016; 28(2):41-47. doi:10.1080/14461242.2015.1086956

Comments