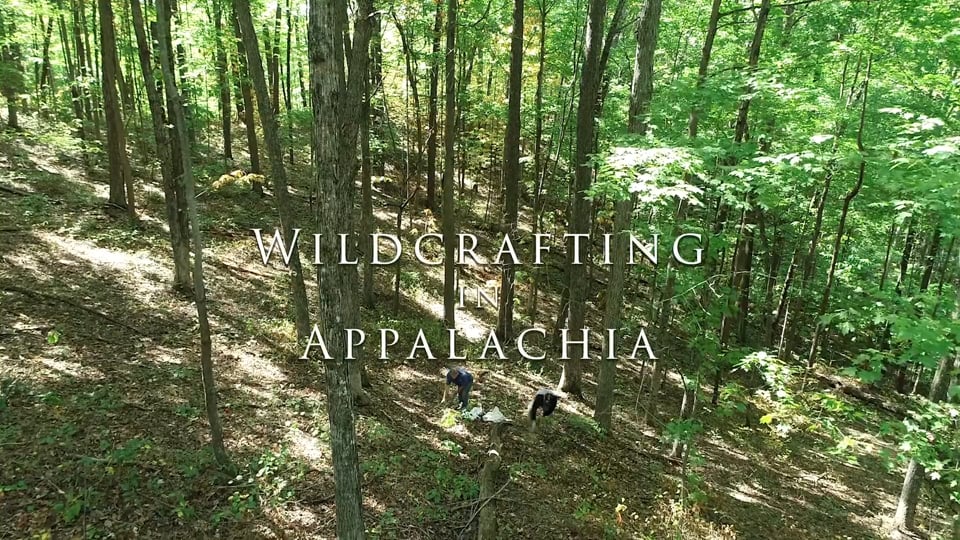

Wildcrafting in Appalachia

Wildcrafting in Appalachia

Ginseng. Goldenseal. Black Cohosh. Blue Cohosh. Slippery Elm Bark. Trillium. These native, perennial forest botanicals grow in moist hollows in the oldest mountains in America, some of the most biodiverse lands in the United States. They are also deeply rooted in Appalachia’s history and intricately woven into the fabric of our culture. Alongside the fur trade, ginseng was a major export of colonial America. The international trade of this economically important herb in the United States dates back to the mid-1700s, with famous early Americans like Daniel Boone.

Steven, SW Virginia. Photo by Ann Armbrecht.

These mountains are also some of the hardest hit economically. First by the logging industries, then coal, and now, in the 21st century, by the opiate epidemic. Harvesting forest botanicals was and is a way to get by when times are tight.

As Ed Fletcher says in the video, “They call this wildcrafting for a reason. I mean, to me it’s a craft. And a craft is an art that you hone over the years.”

How can those of us using finished products made from these botanicals support the livelihoods of those doing the hard work of digging the roots and hauling them to market where they typically make pennies for their labor?

History of Wildcrafting in Appalachia

Calvin Cawles was the first known herb merchant from North Carolina and one of the main herb traders before the Civil War. In “Roots, Barks, Berries, and Jews: the herb Trade in Gilded-Age North Carolina,” Gary Freeze describes how Cawles sold blue flag, lady slipper, penny royal, mandrake, wild indigo root among others, to buyers in all the big eastern cities, including, his records note, “the Shaker gent (?) Robert Sheperd who bought a bale of wild ginger in 1859.”[1]

Hard scrabble farmers in the mountains, men and women for whom herbs were like “found money,” brought a “handful of ginseng or a sack of cherry or slippery elm bark, or a truckload of maypop herb” to a local store or all the way to town on their Saturday shopping trip, where they traded the herbs in exchange for credit at the store.[2] The merchants dried, stored and shipped the herbs to Statesville, NC where the Wallace Brothers sold them to some of the biggest botanical houses in the world in Liverpool, London, Rotterdom, and Amsterdam.[1]

The Lloyd Brothers and the Eclectic schools in Cincinnati, Ohio, was one of the main drug collection centers until after the Civil War. Other domestic buyers included pharmaceutical companies, drug millers, and manufacturers of liquid extracts in Ohio, Iowa, Maryland, New Jersey and New York.[1]

At its height in the late 1800s, one of the biggest raw drug supply houses, the Wallace herb business in Statesville, NC, stored more than 2000 varieties of leaves, roots, barks and berries in their 44,000 square foot botanic debot. In 1883, NC Agricultural Department officials noted that “the bales [of medicinal herbs] seen in the country stores of the mountains were “similar to the bales of cotton seen elsewhere.”

Pikeville, KY. Photo by Steven Foster.

Freeze writes about a visitor’s account in 1884 of strolling “among rows upon rows of ginseng, sassafras, and cherry bark, stacked in baskets or wrapped in bales awaiting shipment.” Freeze noted that locals reported stopping by “just to get a whiff through the window.”[1] By the late 1800s, Freeze writes that “the root trade” which had been “looked upon almost contemptuously” generated more than $50,000 and provided a living to many people.[1]

“Although recent alternative medicine often exhibits a here-and-now mentality,” Freeze concludes, “Herbs have been part of the American market place for most of the nation’s history.”[1]

Dig Deeper

There is a rich history of harvesting and trading roots and medicinal plants from Appalachia. The best way to learn about that history is to explore some of the resources below, which include a mix of recordings, photographs, manuscripts, articles, and novels.

- Tending the Commons: Folklife and Landscape in Southern West Virginia — Curated by Mary Hufford, this extensive collection includes sound recordings, photographs, and manuscripts from the American Folklife Center’s Coal River Folklife Project Collection. The project documented traditional uses of the mountains in southern West Virginia, and explored the cultural dimensions of ecological crisis from 1992 to 1999.

- Historian Luke Manget has a series of presentations based on his dissertation research on root diggers and herb gatherers of Appalachia.

- “Root Diggers and Herb Gatherers: How Wild Plants Shaped Post-Civil War Appalachian Society.“

- “Enclosing the Gathering Commons in Nineteenth-Century Appalachia.“

- “Uncommon Commodity: The Triumph of Ginseng Cultivation in the United States, 1890-1920.“

- “Nature’s Emporium: The Botanical Drug Trade and the Commons Tradition in Southern Appalachia, 1847-1917.” Environmental History 21 (2016):660-687.

- The Smithsonian Folklife Festival features ginseng in 2020. Though in-person event has been canceled, they have collected a series of very well-done historical and ethnographic articles on ginseng and more broadly on the tradition of wildcrafting in the region.

- Read Digging Roots in Appalachia, SHP Director, Ann Armbrecht’s impressions from their trip to southwestern Virginia and eastern Kentucky to produce Wildcrafting in Appalachia.

- Read Forest botanicals: Lessons rooted in history,” by ASD Program Director, Katie Commender, for a short overview of this history.

- One of the most poignant descriptions of the culture of wildcrafting can be found in the character, Mogey, in Ann Pancake’s novel, Strange as this Weather Has Been. This novel, one of SHP Director, Ann Armbrecht’s favorite, tells the story of the fight against mountain top removal in the coal fields of southern West Virginia.

Wildcrafting around the World.

Interested in learning about wild harvesting around the world? Find out more about wild collecting medicinal plants and biodiversity in articles and videos on the SHP site. The FairWild Standard as an international certification to provide sustainably and ethically sourced wild harvested medicinal plants.

References Cited

[1] Gary R. Freeze, “Roots, Barks, Berries, and Jews: The Herb Trade in Gilded-Age North Carolina,” Essays in Economic and Business History 13 (1995): 107-27.

[2] Edward Price, “Root Digging in the Appalachians: The Geography of Botanical Drugs,” Geographical Review 50, no. 1 (1960): 1-20, 20.

Comments