Black Cohosh (Actaea racemosa)

Black Cohosh Uses

Black cohosh root was an important folk medicine for menstrual irregularities and as an aid in childbirth. Adopted in medical practice it had a great reputation as an anti-inflammatory for arthritis and rheumatism; for normalizing suppressed or painful menses; and for relieving pain after childbirth. Black cohosh has been widely used for over 60 years in the prevention and treatment of menopausal symptoms. Efficacy and safety are confirmed by this long-term clinical experience; as well as recent controlled clinical studies.

Black Cohosh Sustainability

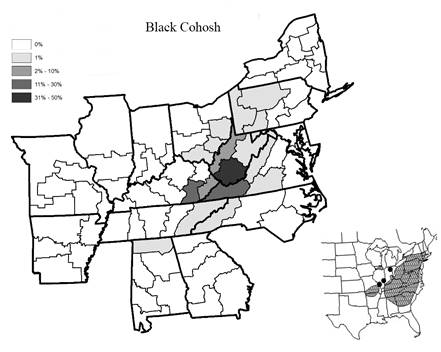

Heat maps depicting trade volumes for goldenseal across 15 states in the eastern US in 2015, represented in percent of total harvest by USFS FIA unit. Results indicate strong centralized tendencies for market activity. Darker colors indicate greater percent of overall trade. [2].

Black cohosh, a member of the buttercup family (Ranunculaceae), is found in rich woodlands of the North American eastern deciduous forest. The striking wand of white flowers distinguish it in gardens and the forest floor.

Although Black Cohosh was withdrawn from consideration for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the vast majority of roots are harvested from wild populations instead of cultivated sources. Among the 10 top-selling herbal supplements in the US in previous years, US retail sales of black cohosh root totaled an estimated $40 million in 2016 and $35 million in 2017 and 2018. As millions of plants are harvested from the wild to meet growing consumer demand, sustainable stewardship and forest farming practices become increasingly important.[1]

Black Cohosh: Post Harvest Handling in Pikeville, KY

This short video produced by the Sustainable Herbs Initiative follows the steps at a direct post-harvest handling processing facility in Pikeville, KY.

Dig Deeper

- Black Cohosh UpS At-Risk page for more information on the conservation status of black cohosh.

- Black Cohosh in Commerce, a two-part series that is part of the SHI Plant in Commerce Series, discusses what is known about the trade of black cohosh and the sustainability of its harvest.

- For a thorough discussion of the history, current use, modern research on black cohosh, see Brinckmann, J. and T. Bender. Herb Profile: Black Cohosh. HerbalGram. 2019;121:6-16.

- For a thorough discussion of economic adulteration of black cohosh, see Foster, S. Exploring the Peripatetic Maze of Black Cohosh Adulteration. HerbalGram 2013;98:32-51 and Gafner, S. Botanical adulterants bulletin on adulteration of Actaea racemosa. Botanical Adulterants Bulletin. 2016.

- See also Brinckmann J. Taking a closer look at the black cohosh rhizome trade from USA. Market News Service for Medicinal Plants & Extracts. 36, 45-51. Reprinted HerbalEGram 2010:7(12).

- Foster, S. Black cohosh. Cimicifuga racemosa. A literature review. HerbalGram 1999; 45:34-49.

- Predny, M.L., De Angelis, P., & Chamberlain, J.L. Black cohosh Actaea racemosa. An annotated bibliography. Asheville, NC: Southern Research Station, 2006:4.

- James Chamberlain; Ness, Gabrielle; Small, Christine J.; Bonner, Simon J.; Hiebert, Elizabeth B. “Modeling below-ground biomass to improve sustainable management of Actaea racemosa, a globally important medicinal forest product,” Forest Ecology and Management 293 (2013):1–8.

- For an overview of black cohosh in commerce, including guidance on harvesting and processing, see Davis, Jeaninie . Black Cohosh: Actaea racemosa L. Mountain Horticultural Crops Research and Extension Center: 2013 (revision of articles written by Jackie Greenfield, Jeanine Davis, and Kari Brayman).

References Cited

[1] Chittum, H., Burkhart, E., Munsell and Krugerm S. “Investing in Forests and Communities: A Pathway to a Sustainable Supply of Forest Herbs in the Eastern United States,” HerbalGram (2019; 124:60-76).

[2] Kruger, S., Munsell, J., Chamberlain,J, Davis, J. and Huish, R. “Describing Medicinal Non-Timber Forest Product Trade in Eastern Deciduous Forests of the United States,” Forests 2020, 11(4), 435; https://doi.org/10.3390/f11040435.