Turmeric in Commerce

A Guest Post by Bill Chioffi

Bill Choiffi is an herbalist with 21 years’ experience with the production of herbal supplements. He is the Director of Botanical Consulting International (for a full bio see bottom).

Bill Chioffi is an herbalist and director of Botanical Consulting International.*

Flooding in India and the impact on Turmeric

Monday August 12th, I received an email from a colleague in India including some news that the turmeric (Curcuma longa, Zingiberaceae), ashwagandha (Withania sominifera, Solanaceae) and tulsi (Ocimum tenuiflorum, Lamiaceae) fields I visited in Karnataka and Maharashtra State in 2017 were under water. Not that surprising as I’ve seen the crop under water in other tropical climates before, it grows near rice paddies in parts of Indonesia. A quick Google search confirmed the problem in that area of India, and I saw pictures of people in Sangli floating around on rafts to safety. I added a mental note of consternation to the running list of environmental disasters that keep piling up.

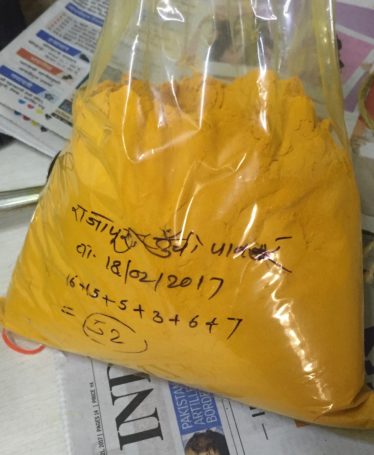

Sangli district in Maharashtra State is well known for turmeric production, particularly the Rajapuri variety. It has also emerged as a wholesale market in turmeric though production is less than 10% of the total in India. It is second to Erode in the state of Tamil Nadu for turmeric production but growing. Don’t forget this trade has been going on for over 2,000 years in India where 80% of the world’s turmeric is grown and consumed. Turmeric, the Golden Spice provides an overview of the traditional and scientific uses of turmeric.

I was compelled to reach out directly to some other connections to see how they were approaching this situation and if their families were all safe. I was shocked to learn that over 1.2 million people had been evacuated and close to 300 were dead due to the recent floods. My sources confirmed that the fields were flooded but in the case of turmeric at least there was hope that the crop would be resilient. They later told me that the waters were receding as of the 18th of August.

A Fluctuating Market

Last year the same regions experienced a drought. Sources indicated that despite the drought there was a strong harvest of turmeric against a declining number of large turmeric contracts. Supply and demand being what they are, this drove the prices of turmeric down. The farmers reacted by asking through their traders for guaranteed minimum pricing. If instituted in the markets, this pricing would allow the farmers to collect a guaranteed minimum price per KG on their crop. This all occurred right around the time of the elections in India as well, with the trader groups trying to leverage off the political climate to gain traction for their movement. The farmers did not achieve their goals and many still worry about making a return on their crop.

In India right now domestic prices for conventional dried turmeric powder are hovering just above $1 per kg domestic and $5 per kg wholesale for export to the US. For perspective, another culinary and medicinal herb, cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum, Zingiberaceae), is selling for around $20/kg in the domestic Indian market. If you are lucky enough to be in an area able to grow vanilla beans(Vanilla planifolia, Orchidaceae, those are selling at upwards of $400/kg from the farm, but that’s a whole different topic.

Synthetic Curcumin on the Market

Although the original email with news of flooding is what prompted my concerns about the ongoing sustainability of high-quality turmeric, it was not the flooding that concerned my sources the most. They went on to describe that a large foreign manufacturing company had recently opened a plant in India and was selling concentrated curcumin extract made from Indian turmeric at a quarter of the current market price. They indicated they were acquiring samples for testing as they were concerned that this material must have been adulterated somehow. My sources manufacture turmeric extract and are well aware of all the various associated operating costs in country. They find it impossible to produce and sell extracts for the prices they were offered.

This leads one to question with even more scrutiny the identity of any curcumin extract purchased. Curcumin is the bright yellow pigment in turmeric, actually a polyphenol, that has been studied for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. It is possible to create a synthetic curcumin at a fraction of the cost derived from petroleum byproducts. The American Botanical Council has released a bulletin outlining the various adulteration issues associated with turmeric. Raw turmeric powders have been identified as containing cassava starch, talc, and artificial yellow dyes added purely for economic reasons.

Testing for Adulteration is not Required

In addition to this type of adulteration by addition, there are over 100 species of Curcuma, yet many may be identified as Curcuma longa on a product package. Manufacturers and distributors of curcumin and turmeric powder can have the materials tested for “synthetic” petroleum based curcumin using sophisticated carbon 14 testing, DNA and macroscopic identification by trained botanists to confirm identity, and other methods for detection of dyes and added starches.

But these tests are not required, and they add additional costs to the product. This tends to drive down profit. Standard costing models used by most large companies buying materials only allow for a narrow range of prices that can be paid for a raw material and still fit into the company’s profit margin formula. These standard costing models are often one of the greatest impediments to purchasing a premium product that has been through rigorous testing and has been through a valued-added process such as organic certification.

See Quality Control for information on the testing required by companies with rigorous quality control standards.

The Turmeric Harvest

Turmeric is planted in the southern part of India around late April or early May and timed with pre-monsoon showers. Depending on which of the many varieties of turmeric are being grown it is a 190-285-day crop. During late January and early February when the harvest begins, the rains have ended and it is hot and dry. Last January the high was 97°F with 100% humidity for the month of February.

The harvesting of turmeric relies heavily on hand labor done in this tropical heat. There is some mechanization but as we will see that golden cluster of mangled roots contains three separate parts to harvest and human sight and experience of those discerning qualities have not yet been duplicated by technology.

Turmeric picker sorting through material with her young one. Maharashtra, India Feb 2017. Photo by Bill Chioffi.

Rows of plants first need to have all the aerial remaining portions removed by machete. These tops are saved, and 4-5 foot piles can be seen scattered throughout the field. Not a single part of the plant goes to waste. The tops will be used to burn for fuel or to cover unearthed roots until they can be further processed in the field. After the tops are removed, a tractor makes one pass with a digging implement to raise the root masses from the ground. I’ve also seen this being done the traditional way with oxen and a plow in Indonesia and India.

Turmeric Fingers

Once the root clusters are loosened the workers, usually women, go through each row on their hands and knees and separate seed, mother rhizome, and “fingers.” The turmeric plant is propagated by root division and it’s necessary to separate the seed by hand since it is attached to the cluster of “fingers” that become the bright spice we all love in our curry. Small wooden hand rakes are used to work the material, which by that time of the season is encased in dry, hard soil.

Turmeric Rake harvesting tool with separated prime turmeric fingers in background. Maharashtra, India Feb 2017. Photo by Bill Chioffi.

The sun bakes the southern Indian landscape for almost 1,000 hours per year. This force of nature allows this spice to cure properly in this early stage of processing. I have seen very few drying facilities at the farm level as they all use solar drying to initiate the drying process.

Once the fingers are all separated from the bulbous mother rhizome and seed, they are taken to a large steam kettle in the field and “boiled” for a short time in order to assist in the next process of field drying by opening up the first layer of “skin” on the outside of the turmeric finger. Moisture can be released more easily and the root dries better in the sun. Processors claim this enhances the brightness of the yellow pigments.

Turmeric Finger Steaming in the field pre-field drying. Green Tarps with roots in background. Maharashtra, India Feb 2017 Photo by Bill Chioffi.

Drying and Polishing Turmeric

Traditional techniques involved laying the turmeric in metal pans and covering it with layers of turmeric leaves and cow dung. The ammonia from the cow dung reacted with the turmeric to produce a similar effect as boiling without the use of heat, fuel, etc. As is so often the case, the traditional technique for processing has a very low environmental impact and is the simplest approach. This practice is not used today for sanitary reasons. Instead, it is now common to burn the cow dung for fuel, you can see big piles of it stacked up on the roads in the countryside.

To finish the process of the harvest, tarps are laid out in the fields and the material from the steam kettle is dried in the sun until it reaches a low enough moisture that allows it to be sent to a processor to finish the job of sorting, polishing, and processing into a powder. The larger, core of the turmeric rhizome cluster known as the “mother rhizome” has a higher percentage of curcumin than the fingers. It is separated and sold to the extractors to make concentrated extracts. The “fingers” from Mahrashtra and Rajasthan are sold mostly for the production of turmeric powder and are sent off to auction markets many located in Sangli, where it is purchased and then further processed into a powder.

Who Harvests Turmeric?

The families working the turmeric fields I visited in Maharashtra did not own any of the fields they were farming. They were working it for a landowner, and this is not uncommon. The families move from the south of India near Tamil Nadu and follow the turmeric harvest north for as long as there is good work. They then return to the south after a couple of months on the road. I was told this has been done for centuries in some families, and that camping next to the fields was quite common. It’s hard work done on or close to the earth which is often baked dry at harvest. Though the workers care little about the sales trends for turmeric and curcumin, their continued ability to work the crop does depend on continued “growth”.

Field workers with turmeric leaves in background. Maharashtra, India Feb 2017. Photo by Bill Chioffi.

Farmers everywhere adapt to weather related issues continuously and have been since the beginning of agriculture. Patterns were easier to predict in the past and in this particular point in time we are experiencing regular extremes of destructive weather. The weather and climate are only part of the puzzle for this crop and its continued sustainability. Economic factors could cause some farms to convert to other more lucrative cash crops. The trade in turmeric and turmeric-derived products is experiencing some slowing in retail sales, possibly because people are trying CBD products for the same kinds of inflammation and pain related issues. This trend looks to continue. Such is the nature of dietary supplements.

Climate Change and Turmeric

Actions that would help the climate and thereby weather-related issues in India and across the globe are many. In terms of agriculture steps that can be taken include checking carbon emissions from farm equipment, limiting deforestation that leads to the loss of soil, and further compaction issues from overworking the land in a non-regenerative manner. Current overly mechanized farming techniques create excess runoff via soil compaction that directly contributes to the flooding and dispersion of pesticides, inorganic fertilizer residues and animal wastes into the aquifer.

Organic and fair trade projects are being developed in India and other turmeric producing countries but often the costs of third-party certification is prohibitive for very small village farmers who lack resources to buy agrochemicals in the first place so they rely on “traditional regenerative” methods for farming simply because of necessity. Guess what? Those methods work better anyway.

Unearthing turmeric root harvest in a highly-productive, regenerative farming operation at Finca Luna Nueva, Costa Rica. Photo by Steven Foster.

What to do?

Many companies are willing to sponsor the FairWild Standard for herbs harvested from the wild or pay for organic, Biodynamic and regenerative certifications on cultivated crops. Getting involved on the ground level helps to determine what a farmer or processor really needs to do to keep up with all the challenges. I am a subscriber and have found the beliefs of my colleague Josef Brinckmann to be true: “Pick a plant and follow it through your supply chain.” It is a great place to start with sustainability. Often opportunities that were not previously considered reveal themselves during this process, one which also ends-up strengthening the relationship with the producers. But it is vitally important to DO something.

I am planning to travel to India and Indonesia for the harvest in order to continue investigating this crop and see some new organic projects. For now, continued prayers go out to all farmers and wild harvesters of plants and the planet in general which is hurting right now and as we are seeing quite capable of self-regulating. Everything is connected. I think of these farmers and can see their worn hands as I measure out tablespoons of golden aromatic powder into a pan of ghee to begin my curry.

* Bill Chioffi is an herbalist with 21 years’ experience with the production of herbal supplements. This includes all phases of vertically integrated botanical manufacturing of liquid extracts and concentrates, international and domestic regulatory and Good Agricultural and Collection Practices (GACP) auditing experience, social responsibility/sustainability management and program development, agroforestry and supply chain development planning, political advocacy, clinical research guidance and education. He is the director of Botanical Consulting International and serves on the following boards; United Plant Savers, Sustainable Herbs Project/ABC (advisory group), Appalachian Beginning Forest Farmers, including past membership on the Executive Committee of The American Herbal Products Association (AHPA) as Vice Chair of the Board of Directors for two terms during his twenty-one-year tenure with Gaia Herbs, Inc. He is currently active in the North Carolina Industrial Hemp Association. It is Bill’s hope that the herbal products industry begins to adopt strict policies on the sourcing of botanicals to protect the environment and the people who work so diligently to raise and collect our plant medicines.

Excellent, thank you! My only comment is to ask for dates to be given in full unless the content is changed/updated annually.

Good suggestion. Thanks!