Lady’s Slipper Conservation – Part I

European Yellow Lady’s Slipper—Towards a Conservation Success Story

By Steven Foster

Pink Lady’s Slipper, Cypripedium acaule.

To read a longer version of this article, see: “Lady’s Slippers: once a Commercial Conundrum, Now a Conservation Success Story” in HerbalEGram, issue 7, July 2021.

It was just over forty years ago, June of 1980, and it was my first year in the Ozarks. It was a time when I was beginning to make friends with Arkansas botanists. One new botanical friend with whom I searched for rare plants was the late Richard H. Davis (1946-1983), a field ecologist for the Nature Conservancy under contract with the Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission. We went to an historic location for the most southwestern population of showy lady’s slipper Cypripedium reginae (Orchidaceae), known in older works as Cypripedium spectable. This lady’s slipper is both a “queen” and a “spectacle” as the species names imply. She is the largest and most impressive native North American orchid. Adopted by Minnesota as its state flower, it grows up to 3 feet tall, with gorgeous 3-inch-wide white to pink-red flowers.

Our search was at the very edge of the plant’s southern range. We meandered up a circuitous creek in the water because the terrain was too rugged to do otherwise. Reaching the location noted on an herbarium specimen 40 years earlier, we spent the better part of a day looking for the orchid without success. Disappointed by our failure, we headed back down stream. Then much to our surprise, there it was growing about ten feet up on a narrow limestone shelf—the showy lady’s slipper was in full bloom.

Appreciating Lady’s Slippers

In the search for rare plants, such moments evoke ecstasy, like meeting an old friend, or a famous person you’ve only heard about. Lady’s slippers’ beauty, enamor humans—sometimes too much. Their beauty invites some to pluck them from the wild to embellish a vase, enhance a garden, or harvest the root for traditional herbal uses.

In a series of articles on “wild plants needing protection” published in 1913 issues of the Journal of the New York Botanical Garden, Elizabeth G. Britton warned that the “pink moccasin flower” was formerly found in wilder portions of greater New York and Staten Island, “but is becoming extinct, on account of its showy flowers, which are usually plucked close to the root…” [1]

Where I grew-up in southern Maine most people are familiar with pink lady’s slipper or pink moccasin flower (Cypripedium acaule). As a child I recall picking a pink lady’s slipper for my mother. Instead of delight, she roundly scolded me for my act of generosity, warning me not to pick it again. “It’s illegal,” she exclaimed. Of course, it wasn’t illegal, but my generation grew up with the ethos that you just don’t pick lady’s slippers. Above all, they’re too rare, too special to disturb.

Richard H. Davis (1946-1983), late botanist for the Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission, at the rediscovery of Showy Lady’s Slipper, Cypripedium reginae, in Arkansas, June 1980.

The Genus Cypripedium

There are 52 species in the genus Cypripedium, 12 from North America; Central America, Europe, and temperate Asia, particularly China, where 25 species are endemic. Most of the eastern North American species were known to Europeans soon after their arrival. Botanists described six western North American species in the early to mid-nineteenth century. Cypripedium combines two Greek words, one honoring Cyprus, the birthplace of the mythical Aphrodite (Venus) and pedium “foot or slipper” (Aphrodite’s slipper) alluding to the inflated shape of the flower lip.[2]

Europe’s Yellow Lady’s Slipper

The single northern European species of lady’s slipper, the European yellow lady’s slipper (Cypripedium calceolus) is the poster child—the flagship species—of plant conservation in Eurasia. One of Europe’s most studied plants from a conservation biology perspective, it has a broad range which includes most of Europe, the Crimea, Mediterranean, Asia Minor, western and eastern Siberia, to the eastern edge of Russia, south of Sakhalin Island. Recently discovered in the Djurdjura mountain range in north-central Algeria, its known range for the first time now extends to North Africa.[3] The plant was much more widespread in the nineteenth century, along with habitat loss, it declined due to over-collection for horticulture.

England’s Poster Child for Plant Conservation for Four Centuries

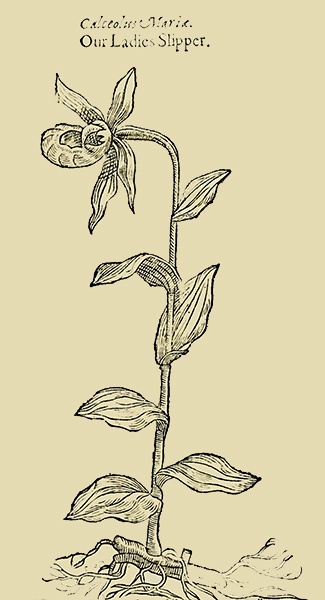

Lady’s Slipper, 1597 Gerard’s Herball

For 400 years, the primary threat to the European yellow lady’s slipper has been the desire to dig it to sell at horticultural markets or transplant into gardens. Botanical and herbal authors from the end of the Renaissance to the early years of the Age of Enlightenment commented on the occurrence and decline of the European yellow lady’s slipper, including leading English herbal writers.

John Gerard (1564-1637) admitted in his 1597 Herball or Generall History of Plants that he grew wild-dug lady’s slippers in his garden. “Ladies slipper groweth upon the mountaines of Germanie, Hungarie, and Poland. I have a plant thereof in my garden, which I received from Master Garret Apothecarie my very good friend.”[4] Although a curiosity as a garden plant, the European yellow lady’s slipper found no use in herbal practice. “Of our Ladies Slipper or our Ladies Shooe,” John Gerard writes, “Touching the faculties of our Ladies shoo, wee have nothing to write, being not sufficiently known to the older writers, no not to the new.”[4]

Two hundred years later, conservation concerns emerged. Dr. William Withering (1741-1799) famous for introducing foxglove leaves (Digitalis purpurea; Scrophulariaceae) as a cardiac drug, writes in the second edition of his A Botanical Arrangement of British Plants, “I searched for it in vain in Helk’s Wood, a gardener of Ingleton having eradicated every plant for sale…”[5]

A Challenge to Propagate

Despite their seductive alure, terrestrial orchids are notoriously challenging to propagate, grow, and coax to thrive. The challenges start with the plants’ complex reproductive biology. The seeds are like dust, nearly microscopic. A single orchid fruit may hold tens or hundreds of thousands of seeds. Their tiny size provides very little nutrient reserves in the seeds themselves. Therefore, they only germinate in association with compatible mycorrhizal association, both at the germination stage and until seedlings develop.[6]

The reproducing plant tissue adheres to mycorrhiza beneath the soil surface for several years before leaves appear above ground. This obligate relationship between lady’s slipper seed and soil fungi is essential for the orchid’s survival and was observed as early as 1824 by German botanist Heinrich Friedrich Link (1787-1851), director of the Berlin Botanical Garden from 1815-1851. Results were first published in his Elementa Philosophiae Botanicae. In later works he produced detailed drawings of mycorrhiza within germinating seeds and seedlings of a tropical orchid.[7]

The tiny seedlings of many orchids are simply a small mass of white tissue below ground, tended by the mycorrhizal filaments which supply water, minerals, and carbohydrates until finally after several years, it produces above-ground leaves and becomes self-sufficient through photosynthesis.[8]

Today’s Conservation Focus

Before raising the alarm to save the plant from extinction in England—complete with 24-hour police protection by 2010—that country’s wild yellow lady’s slipper population declined to a single plant in the Yorkshire Dales by the 1930s! Through the efforts of a tissue culture lab at the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew, it has been re-established at 11 sites in its former range, and two of the sites are accessible to the public for chaperoned viewing.[9]

In the Netherlands a conservation effort including landowners, green groups, local authorities, scientists, and media resulted in the mass propagation and marketing of C. calceolus.[10] The European yellow lady’s slipper is making a still tenuous comeback. Now climate change comes into play in determining the plant’s future, with up to 63% habitat loss coupled with the loss of suitable niches for the plant’s two dozen pollinators predicted by 2070.[11]

In conclusion, since the 1990s, advances have been made in the propagation of Cypripedium species by seed and through tissue culture and other breakthroughs in micropropagation techniques. Interaction with soil mycorrhizal fungi and dependence on specialized pollinators make terrestrial orchids vulnerable to human activities and climate change.[12] The perception that humans should simply leave lady’s slipper orchids alone in the wild seems to have taken hold.

In part II we will explore the natural history and medical history of the eastern North American species of lady’s slippers.

References:

- Britton EG. Wild Plants Needing Protection. No. 7. Pink Moccasin Flower. Journal of the New York Botanical Garden. 1913;14(May):97-99.

- Cribb P. The Genus Cypripedium. Portland, OR: The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and Timber Press. 1997.

- Nemer W, Rebbas K, Krouchi F. Découverte de Cypripedium calceolus (Orchidaceae) au Djurdjura (Algérie), nouvelle pour l’Afrique du Nord. Medit. 2019;(29):207-14.

- Gerard J. The Herball, or Generall histories of plantes. London: John Norton; 1597:359.

- Withering W. A Botanical Arrangement of British Plants. Birmingham, England: M. Swinney; 1787; Volume II:1001-2.

- Swarts ND, Dixon KW. Terrestrial orchid conservation in the age of extinction. Annals of Botany. 2009; 104:543-56.

- Link HF. Elementa Philosophiae Botanicae. Berolini: Haude et Spener; 1824.

- Yam TW, Arditti J. History of orchid propagation: a mirror of the history of biotechnology. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2009;3:1-56

- Cole S, Waller M. Britain’s orchids: a field guide to the orchids of Great Britain and Ireland. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2020.

- Gale SW, Fischer GA, Cribb PJ and Fay MF. Orchid conservation: bridging the gap between science and practice. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 2018;186:425-34.

- Kolanowska M, Jakubska-Busse A. Is the lady’s-slipper orchid (Cypripedium calceolus) likely to shortly become extinct in Europe? —Insights based on ecological niche modelling. PLoS ONE. 2020:15(1):1-21.

- Fay MF, Chase MW. Orchid biology: from Linnaeus via Darwin to the 21st century. Annals of Botany. 2009; 104:359–364.

European Yellow Lady’s Slipper. Adapted from: Redouté PJ, Les liliacees. vol 1. Paris: Chez l’auteur; 1805

Comments