Conference Highlights: Why Using Sustainable Herbs Matters

Highlights by Ann Armbrecht, SHI Director.

On April 7, 2023, with the Herbal Alliance, the then Sustainable Herbs Program co-hosted a half-day conference, Why Using Sustainable Herbs Matters. Sebastian Pole, founder of Pukka Herbs and trustee of the Herbal Alliance, and I organized this event to bring together experts in sourcing and quality to discuss how ethical sourcing is important not only because it is the right thing to do for the people, plants and planet, but responsible sourcing is critical because it helps ensure that:

- The herbs in the bottle are what the label claims they are;

- Those herbs are of the right quality with the right balance of constituents shown to have the effects that the product is said to have; and

- Other ingredients, dyes, chemicals, etc. are not in the bottle.

As the speakers made clear, the most effective and cost-effective path is to address these issues at the source, especially by investing in the relationships needed to ensure that people will take care at each step of a plant’s journey from seed to finished product.

Some of the highlights of the conference follow. This is by no means a thorough summary of key points discussed. As Anastasiya Timoshyna, Director of Strategy, Program, and Impact at TRAFFIC, said, “Not knowing is not an answer anymore.” If you missed the conference, I encourage you to watch the presentations here. Your purchase (for $10) supports our ongoing outreach from the conference.

We are all Connected by the Herbs

Sebastian opened the conference by saying, “We know we’re in the middle of many challenges with the climate and with challenges with health, individually and socially. As herbalists, as clinical practitioners or those working in the herbal community and industry, we’re the repositories of this incredible knowledge, these amazing traditions and this wisdom. We have an opportunity to join together to find a way to bring better solutions to our community in terms of the sustainability of the plants we’re using and the communities we work with.”

“Before this talk,” Sebastian said, “I was reflecting on how interconnected we are by the global value chain. Although we’re in different countries, the herbs that we use and that use in our clinics will be coming from similar places. In this way, we’re all connected through this value chain.”

The Impacts of the Herb Trade are a Choice

He continued by saying that one quarter of plants in trade come from the wild. That’s billions of kilos. This trade can be positive and lead to some great conservation and sustainable livelihood actions. Or, he said, it can be negative and lead to degradation if the demand outstrips the capacity of the plants to regenerate and exploits the harvesters. Our questions and our choices make a difference in which of those impacts this trade will have.

What Practices Enable Sustainable Use?

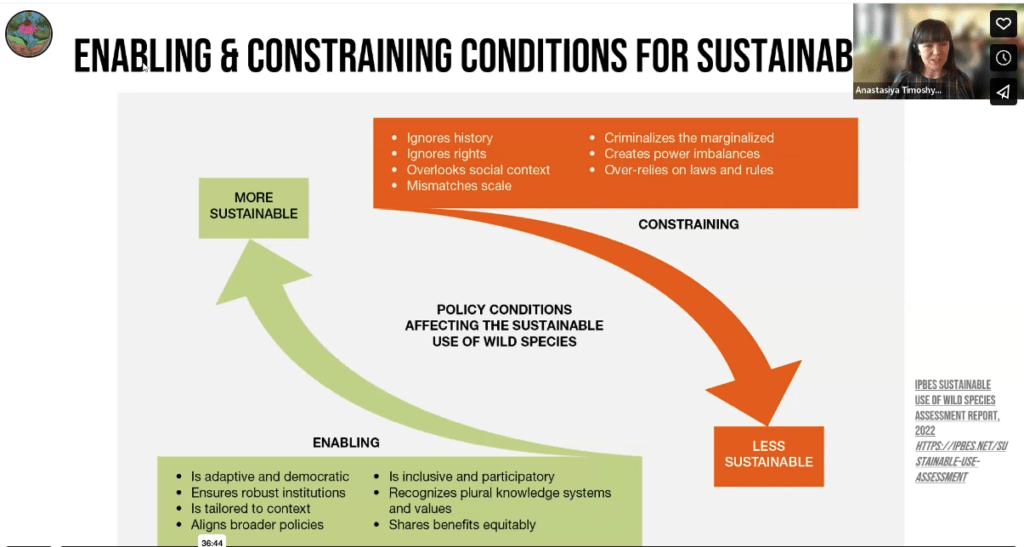

In her talk, Anastasiya Timoshyna of TRAFFIC shared a number of interesting statistics on wild plants from the 2022 IPBES Sustainable Use of Wild Species Assessment Report. I was especially interested in this diagram outlining the practices that enable sustainable use.

These practices are important because they demonstrate that it is not just what we do to address the threats to wild plants and biodiversity. How we do them: the relationships we build, the institutions created, and how we maintain these institutions matter alongside the actual tools. These practices include systems that are adaptive and democratic, which in turn ensure robust institutions; use that is tailored to the context; are participatory and inclusive, recognize plural knowledge systems, and share benefits equitably.

Quality and Sourcing

Ethnopharmacologist Anthony Booker presented his research looking at the relationship between quality and sourcing practices. He compared the HPTLC chromatograms of products (found online from Amazon) for Ginkgo biloba, Rhodiola rosea, milk thistle, St. John’s wort, and turmeric. With every species they found dramatic differences in the range of quality between the products and the reference samples. Some products had hardly any of the active ingredient, which he said could be due to incorrect extraction techniques or poor quality raw materials. Others, for example ginkgo, had incredibly high levels of one compound, rutin, compared to the reference sample. He said that this is likely because companies added rutin to the excipient to boost its levels so they could make certain claims on the bottle.

In another example, they compared HPTLC graphs of 20-30 milk thistle products. Some had no sylimarin, the active ingredient in milk thistle. Others were low quality compared to the sample, and one bore no resemblance to the reference sample.

It’s difficult to find quality, he said. And he recommended first, asking whether a company knows where their herbs are from. Most can’t say. It is important to know more than whether the herbs are from a market somewhere in India or China. Ask if they know the farmer? Is there any kind of integrated chain? That is very important.

Secondly, certified organic is important. If a company has gone to the trouble of getting a certification, they’re not as likely to be adding adulterants to their products.

See more about the implications of this research in the SHP blog post and webinar, How Sourcing Botanicals Impacts Product Quality

What Does Fair Trade Mean?

Fair certifications are slowly gaining more momentum in the herb industry. Yet it can be difficult to know what difference those labels make, especially amidst accusations (often correct) that fair trade is still not translating into a living income for many workers. Erin Smith, VP of Herbal Science & Research at Banyan Botanicals, shared specific ways that becoming B Corps and Fair for Life certified has made a difference in how Banyan Botanicals does their work.

What To Do

- Buy fair trade herbs. This can directly impact their availability.

- Educate clients to know where their herbs come from and the differences between sustainable and fairly traded herbs and conventional ones.

- Ask questions. If a company can’t answer them, find another company.

For more on Erin’s talk, see the SHP blog post, How Fair is the Herbal Supply Chain??

Read this case study with Doselva and Gaia where Nicaraguan coffee farmers are adding turmeric and ginger to their coffee farms to diversify the products they can sell and thus increase their income.

Migrant Farm Workers

Alison Czeczuga, director of social impact and sustainability at Gaia Herbs, described the work Gaia is doing to go beyond the H2A visa program to protect their farmworkers. H2A, the federal program which allows foreign nationals to enter the US to perform agricultural work, has come under recent criticism for rampant abuse of the program.

The farmers are the land stewards on their farms. They bring specialized knowledge to the growing and harvesting of medicinal plants and the H2A program doesn’t go far enough in supporting their work. Gaia is addressing these limitations in four ways:

- Improve their wages and benefits

- Improve transportation to their homes since traveling between Mexico and North Carolina can be dangerous.

- Design and construct farmworker housing. They are now staying in a place where there are safety concerns, so Gaia has invested $1 million in addressing those problems.

- Health and advocacy program. They are working with a group that is focusing on farmer worker health to address that.

In the first year, they met all their goals except for farmworker housing; this is taking longer, in part because they went through a participatory process to include farmworkers in the design and are now working to implement those changes on the farm.

Challenges to Sourcing Herbs

Josef Brinckmann, Research Fellow, Medicinal Plants and Botanical Supply Chain’ for Traditional Medicinals, outlined the threats to sourcing herbs. These include contamination and labor shortages through areas where plants are harvested. The plants are there in many places, he said, but there are no people to do the work. Pollinators are disappearing. If they go, we go. Geopolitical unrest and wars are also disrupting supplies of herbs from around the world.

In closing, Josef said that practitioners can source herbs by trusting certifications. It can be daunting, he said. Start out with a few and go one at a time. It can be harder to do this for individual practitioners than companies because a company has more leverage and access to the suppliers.

Assessing Quality

Roy Upton, founder of the American Herbal Pharmacopoeia, took us back to the 17th-18th centuries when the herbalist’s interface with the patient was the primary way to assess quality, and therefore efficacy. If the herbalist was good at what they did, they survived as a practitioner. If they weren’t good, they didn’t.

The quality of diagnosis as well as the quality of medicine that they were producing and dispensing determined that outcome.

In 1803 the active constituent morphine was derived from the opium poppy, which Roy said was a major demarcation in the history of medicine. After that, practitioners no longer had to use the whole plant. This started the search for active compounds which changed how quality was defined.

The challenge now, Roy explained, is finding and maintaining a direct connection with where plants come from, who’s growing them, who’s harvesting them, and whether these plants are being sourced in a sustainable way. Also, the challenge is how to blend the mission of herbalism that is centered around the plants with the scientific inquiry requirements of modern regulatory challenges.

Treating the Earth as A Commodity

Herbalist David Winston perhaps summed up the challenge most eloquently in his closing comments, which I include here in full,

“I would say seeing the earth as separate or as a commodity creates a mindset that has been called nature deficit disorder or species loneliness. It separates us from the real world, from the natural world. And I believe it leads to our feelings of disconnection, anxiety, and depression. If you are a clinician right now, certainly over the last three years, one of the things you’re seeing over and over and over again in your patients, is depression, anxiety, and loneliness.

So I think that again, seeing the earth as a living thing that we are a part of, and respecting that, and using medicines that are fresh, and organically cultivated, helps to heal us, not only physically and emotionally, but spiritually as well.”

What is the Next Thing You Can Do?

We asked the participants to write in the chat what the next thing they can do to support sustainable and ethical sourcing is. Everyone agreed: connect, collaborate, share information, increase access to knowledge so that everyone can understand the impact of our choices.

We will be sharing more information from the conference and following up in different ways, including developing a Buyer’s Guide to Herbal Products and a curriculum module on Sustainable Sourcing. In the meantime, see the SHI curriculum and practitioner guidelines here.