A Trip Report by Ann Armbrecht, SHP Director

In September 2019, Terry Youk and I traveled to the heart of Appalachia—southwestern West Virginia and Virginia and eastern Kentucky—to film a series of short videos to raise awareness about forest botanicals from Appalachia in collaboration with Katie Commender and the Appalachian Harvest Herb Hub. Appalachian Sustainable Development’s Appalachian Harvest Herb Hub facility, based in Duffield, VA, provides seed to sale training, shared-use commercial herb processing equipment, and aggregation and marketing services to forest farmers in Central Appalachia. In Kentucky, Steven Foster joined us. We also filmed more broadly on the supply networks of botanicals from Appalachia and met with buyers and diggers from the region. As we transcribe the interviews and log the footage I will share more.

Note: The issues relating to the supply of botanicals from Appalachia are complex, involving a nexus of economic, cultural, political and ecological factors that have shaped and continue to shape the supply networks and how they are changing. Black Cohosh in Commerce talks about the economic and ecological aspects of this trade. The second of this two-part series, Economics of Black Cohosh, introduces the forest grown program and the FairWild standard as two potential models for addressing the ecological sustainability of forest botanicals. This current post largely focuses on our conversations with the ginseng dealers and wild harvesters we were able to interview on our recent trip. A future post will focus on our interviews with forest farmers.

Appalachian Supply Networks

On this trip, we drove through Williamson on our way to Grundy, VA, passing boarded up store fronts, run down houses. The last time I’d been to this corner of West Virginia was in 8th grade. I’d driven down from my home in Charleston, WV with my church youth group to help with the clean up after devastating flooding in the 1970s. Over forty years later, I still remember the rank smell of the two feet of mud we shoveled from the downtown streets and the blackened faces of coal miners walking home from their shifts underground.

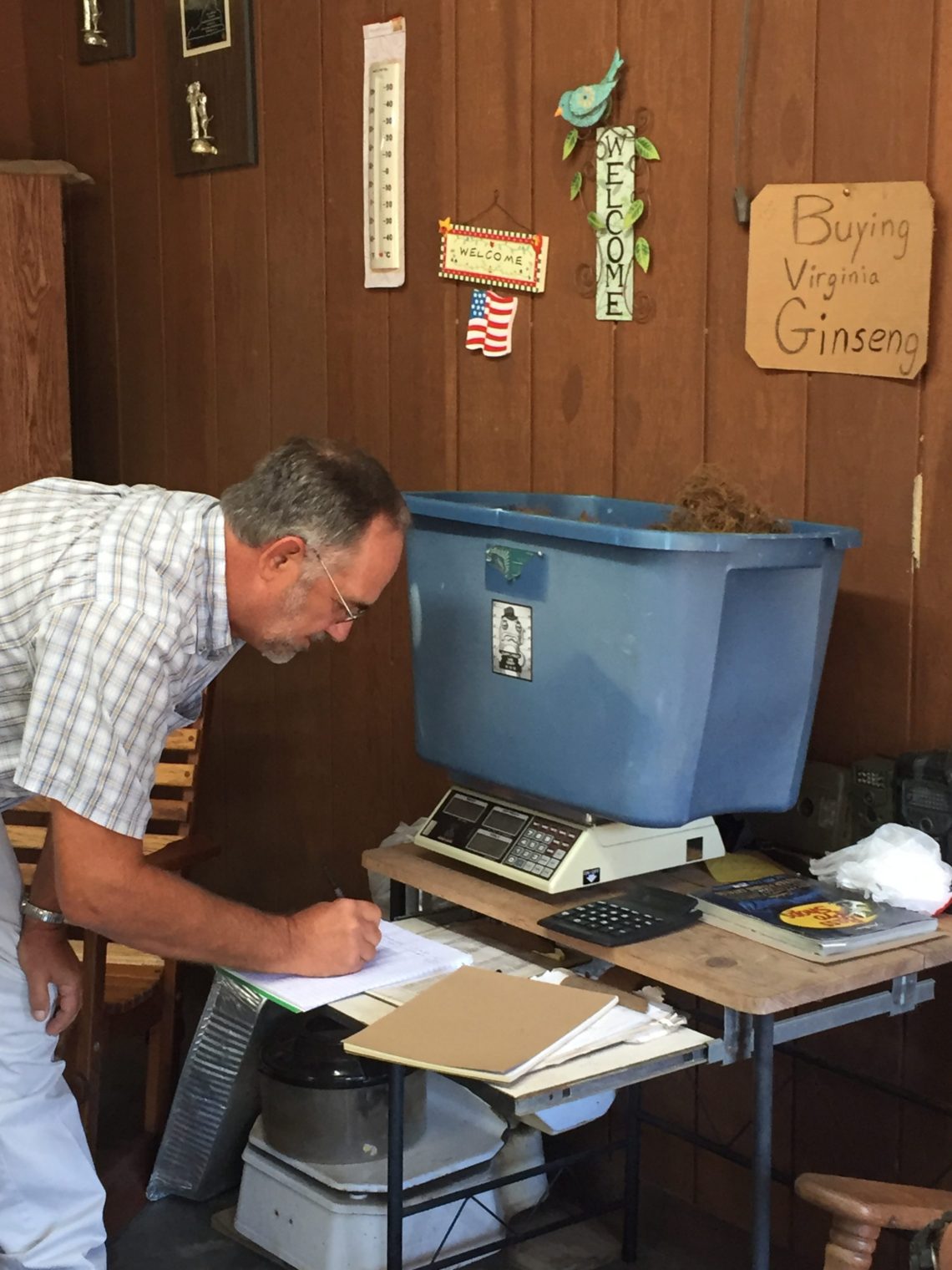

The ginseng season had just opened and so while I’d hoped to film black cohosh harvesting, we instead met diggers bringing in small sacks or trays of ginseng root, hoping to sell it for $550/lb., to buyers. Digging black cohosh, which sells for around $5/lb. was the last thing on their mind. We also met new forest farmers working with the Appalachian Harvest Herb Hub who see replanting the forest as a way to revitalize this region and to provide an economic incentive to conserve the land.

No One to Dig the Roots

It hadn’t rained in a month and the temperatures were in the 90s. The season was slow. The heat was keeping people from digging, the buyers speculated. The very dry forests were making the ginseng leaves dry up, leading diggers and buyers alike to predict it would be a short season. Dry soil also makes it much more difficult to dig, as tools simply don’t easily penetrate the hardened soil. The drought also risked drying up the black cohosh leaves and stalks, which would make the plants harder to find in the winter months, when those who do collect black cohosh often went to the woods to find it.

Since mining had slowed down in the region, more and more people are moving away (see Hollow, an interactive documentary for a moving account of outmigration in this region). There were fewer people to go to the woods. There used to be 17 diggers in a two-mile area from his home, Paul*, the buyer told us, who we visited with Ed Fletcher. Cars would line up the road beginning at 4 am on the first day of buying ginseng. The diggers would talk about their day, the weather, the woods, and how they came across the ginseng. Those people are all too old now, Paul continued, too sick to go to the woods, their bodies broken from a lifetime working underground. Now there is only one person who digs in that two-mile stretch.

We were there on the first day this year, people came, but one at a time, and there were no lines and few stories.

Moving Away

Steven, Paul’s son-in-law who worked with Paul, told us these days no one is willing to do the work needed to dig, climbing steep slopes hauling a sack of roots, only to come in, in the case of all roots other than ginseng, and make $50 for a hard day of work. Those who weren’t moving away, were taking jobs at Walmart or gas stations, jobs where you could stay inside all day and where the pay was steady. Or they follow hurricanes and work in construction where the pay is higher. Often the younger generation is too busy inside playing games, Steven demonstrated his thumbs moving on a device, not able or willing to use a mallet.

The opiate crisis has hit this region, and affected the traditional Appalachian wild-harvesting trade, hard. It’s difficult to find students who are curious and motivated, a school teacher told us. The only role models they had were their parents, most of whom were addicted to drugs. A parent said that her children were some of the few in their school with both parents. Most others had lost at least one and often both to an overdose and were being raised by their grandparents.

It’s hard to figure out what to hope for in Appalachia, what will bring about the changes needed to revitalize communities that seem to have been on the wrong side of capitalism for as long as capitalism has been around. Even during the heyday of this region, when the mines were operating to capacity, a time many remember now as a kind of paradise, the wealth of the region was being exported, the profits invested elsewhere, not back into this region to build capacity, or to diversify the economy for the eventual time when coal mining ended.

“I Love It”

I was most moved by the memories of those who grew up in the forest. They went there to dig roots but, unlike coal which was always only about making an income, once in the woods, they discovered so much more.

Joe, a man in Kevlar pants to protect against the copperheads and rattlesnakes, remembered the first time his “pawpaw” (not to be confused with the fruit) took him to the woods. He was 6 or 7 at the time. His father showed him what to look for to find a ginseng plant and then took him to a spot and told him to stay there until he found the ginseng. Joe stayed there all night long. His father stayed further up in the woods, keeping an eye on him but leaving him on his own. His brother couldn’t take it, Joe said. He ran back home. But Joe spent the night there. In the morning he found the ginseng plants.

“I love it,” he said, his words clipped short and with a strong Appalachian accent. “If I have a job, I quit, just so I can go digging.”

He had a ginseng plant that his “pawpaw” grew, he added. He’s going to keep it, for sentimental reasons, he said. As he climbed onto his ATV to head back into the forest to dig more roots, he told Zac a member of the Pentecostal church of snake handlers, that he had a snake in his bathroom at home if Zac wanted to buy it for $100.

I’d come to Appalachia mostly thinking about the plants and whether they were being over harvested. Yet, as with my trips to eastern Europe, I came away with the strongest impressions of the people.

Being Tested

We spent two days with two men from longtime herb trading families. Nils Mueggenburg contacted Nathan Lockard through an old standing mutual contact – the Wilcox’s. The three met and formed a partnership, the Appalachian Herbal Company.

Brandy and Nathan Lockhard, Anne Mueggenburg, Steven Foster, Terry Youk, Ann Armbrecht and Nils Mueggenburg at the Appalachian Herbal Company waterfall.

Over lunch at a Subway, the only restaurant in the small town in Harlan County where we had come to meet some of Nathan’s buyers, Nils and Nathan talked about their first memories entering warehouses filled with sacks of drying plants, shipped from around the world. Nathan remembered how traders would test his knowledge by seeing what he could identify. Nils described the first task he was given by his father when he was in middle school, of mixing saw palmetto extract with an oil, a job so nasty he imagined his father couldn’t ask any of the paid workers to do it. Nils thought it was also something of a test to see if he was really cut out for this business or not. He guesses he passed, he added.

Hard Work

Digging roots in the hills of Appalachia is hard. The hills are steep and rocky. The snakes are bad. You haul sacks of roots down or up those same steep hills, carry the sack to a buyer, only to find out the 50 lbs. you were hauling had 20 lbs. of soil and rock and your takeaway was only ½ of what you thought. Or worse, that you harvested the wrong plant.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Nathan said, remembering a teenager who brought in the wrong roots, expecting to leave with money for the 4th of July only to go away empty handed.

“What did you do?” I asked.

“Explain how to do ID the plant the right way,” he said. It’s important to be encouraging, he added, so they’ll try again. But he also couldn’t buy the wrong plant.

Sustainability in Appalachia

The plants aren’t what is threatened, Nathan said, echoing what other buyers told us as well. Paul had also told us there were plenty of plants in the woods, adding, “I just don’t have people to dig them.”

Nils said that sustainability in Appalachia isn’t really about the plants. It’s about sustaining the traditions that have in turn sustained the plants, people who learned from their father and grandfather before him how to harvest and when to harvest to make sure the plants were there the next year and the year after that. That knowledge is what is being lost and that’s what they are working to preserve by offering secure and stable markets for those who still want to go into the woods to harvest roots.

The harvesters we spoke with did say it is getting more difficult to find forest botanicals in the woods, particularly ginseng and goldenseal, and that they have to hike farther and farther into the woods to find the plants. Plant population assessments (NatureServe Explorer, IUCN and UpS listings) also show a decline of certain species which, coupled with growing or even a steady demand, threaten the longterm sustainability of these species. As Katie Commender said, “The farther people have to walk to harvest the same volume, the less money they make, and the more desirable Walmart jobs become.”

As elsewhere in the world, the loss of plants and cultural heritage are interconnected. And any solutions must address those connections.

*At their request, I have only included first names of some of those with whom we spoke.

we have 8 of us in our group of gathers but were not making enough to continue on we wre needing contracts on any wild herb you may want harvested legally gensang black and blue cohosh goldenseal or yellow root wild yams stone root and so on. or bark or sasafgrass root bark we are very expierienced and go every day but no one pays the gatherers enough im trying this approuch hoping to get a contract or better pay thank you for your time

I have 68 acres of some of the supposed best sang hills, I bought this land not knowing anything about this region, I grew up foraging in Washington state. I would love to have a class given here with myself attending and being the hostess for the instructor. I am in Knott County Kentucky